Abstract

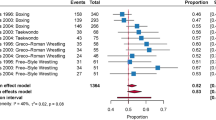

The Olympic Games claim to be exemplars of sustainability, aiming to inspire sustainable futures around the world. Yet no systematic evaluation of their sustainability exists. We develop and apply a model with nine indicators to evaluate the sustainability of the 16 editions of the Summer and Winter Olympic Games between 1992 and 2020, representing a total cost of more than US$70 billion. Our model shows that the overall sustainability of the Olympic Games is medium and that it has declined over time. Salt Lake City 2002 was the most sustainable Olympic Games in this period, whereas Sochi 2014 and Rio de Janeiro 2016 were the least sustainable. No Olympics, however, score in the top category of our model. Three actions should make Olympic hosting more sustainable: first, greatly reducing the size of the event; second, rotating the Olympics among the same cities; third, enforcing independent sustainability standards.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The dataset and statistical analysis are available in the mega-event dataverse on Harvard dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZARR6A.

References

Olympic Marketing Fact File (IOC, 2019).

Wade, S. & Yamaguchi, M. Tokyo Olympics say costs $12.6B; audit report says much more. AP NEWS (20 December 2019); https://apnews.com/eb6d9e318b4b95f7e53cd1b617dce123

Flyvbjerg, B., Budzier, A. & Lunn, D. Regression to the tail: why the Olympics blow up. Environ. Plan. A https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20958724 (2020).

Müller, M. The mega-event syndrome: why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 81, 6–17 (2015).

Sachs, J. D. et al. Six transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2, 805–814 (2019).

Roy, A. & Deshmukh, R. Events Industry Market: Opportunities and Forecast, 2019–2026 (Allied Market Research, 2020).

Poynter, G., Viehoff, V. & Li, Y. (eds) The London Olympics and Urban Development: The Mega-Event City (Routledge, 2015).

Viehoff, V. & Poynter, G. Mega-Event Cities: Urban Legacies of Global Sports Events (Routledge, 2016).

Kraas, F. et al. Humanity on the Move: Unlocking the Transformative Power of Cities (German Advisory Council on Global Change, 2016).

van Vliet, J. Direct and indirect loss of natural area from urban expansion. Nat. Sustain. 2, 755–763 (2019).

Hayes, G. & Horne, J. Sustainable development, shock and awe? London 2012 and civil society. Sociology 45, 749–764 (2011).

Gaffney, C. Between discourse and reality: the un-sustainability of mega-event planning. Sustainability 5, 3926–3940 (2013).

Boykoff, J. & Mascarenhas, G. The olympics, sustainability, and greenwashing: the Rio 2016 summer games. Capital. Nat. Social. 27, 1–11 (2016).

Hall, C. M. Sustainable mega-events: beyond the myth of balanced approaches to mega-event sustainability. Event Manag. 16, 119–131 (2012).

Geeraert, A. & Gauthier, R. Out-of-control Olympics: why the IOC is unable to ensure an environmentally sustainable Olympic Games. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 20, 16–30 (2018).

Liang, Y.-W., Wang, C.-H., Tsaur, S.-H., Yen, C.-H. & Tu, J.-H. Mega-event and urban sustainable development. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 7, 152–171 (2016).

Meza Talavera, A., Al-Ghamdi, S. G. & Koç, M. Sustainability in mega-events: beyond Qatar 2022. Sustainability 11, 6407 (2019).

Mol, A. P. J. & Zhang, L. in Olympic Games, Mega-Events and Civil Societies: Globalization, Environment, Resistance (eds Hayes, G. & Karamichas, J.) 126–150 (Palgrave, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230359185_7

O’Brien, D. & Chalip, L. in Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy (eds Woodside, A. G. & Martin, D.) 318–338 (CABI, 2008).

Olympic Agenda 2020+5 (IOC, 2021).

IOC Sustainability Strategy (IOC, 2017).

Sport as an Enabler of Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly, 2018).

UN and Tokyo 2020, leverage power of Olympic Games in global sustainable development race. UN News (14 November 2018); https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/11/1025711

Vanwynsberghe, R. The Olympic Games Impact (OGI) study for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games: strategies for evaluating sport mega-events’ contribution to sustainability. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 7, 1–18 (2015).

Müller, M. et al. Dataset: Sustainability of the Olympic Games (Harvard Dataverse, 2021); https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZARR6A

Houlihan, B., Bloyce, D. & Smith, A. Developing the research agenda in sport policy. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 1, 1–12 (2009).

Zifkos, G. Sustainability everywhere: problematising the ‘sustainable festival’ phenomenon. Tour. Plan. Dev. 12, 6–19 (2015).

Chappelet, J.-L. Beyond legacy: assessing Olympic Games performance. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 4, 236–256 (2019).

O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F. & Steinberger, J. K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 1, 88–95 (2018).

Neumayer, E. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms (Edward Elgar, 2003).

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly, 2015)

Adoption of the Paris Agreement FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1 (UNFCCC, 2015).

Getz, D. Developing a framework for sustainable event cities. Event Manag. 21, 575–591 (2017).

Smith, A. Theorising the relationship between major sport events and social sustainability. J. Sport Tour. 14, 109–120 (2009).

Minnaert, L. An Olympic legacy for all? The non-infrastructural outcomes of the Olympic Games for socially excluded groups (Atlanta 1996–Beijing 2008). Tour. Manag. 33, 361–370 (2012).

Horne, J. & Whannel, G. Understanding the Olympics (Routledge, 2016).

Smith, A. Events and Urban Regeneration: The Strategic Use of Events to Revitalise Cities (Routledge, 2012).

Panagiotopoulou, R. The legacies of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games: a bitter–sweet burden. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 9, 173–195 (2014).

Searle, G. Uncertain legacy: Sydney’s Olympic stadiums. Eur. Plan. Stud. 10, 845–860 (2002).

Gold, J. R. & Gold, M. M. ‘Bring it under the legacy umbrella’: Olympic host cities and the changing fortunes of the sustainability agenda. Sustainability 5, 3526–3542 (2013).

Holden, M., MacKenzie, J. & VanWynsberghe, R. Vancouver’s promise of the world’s first sustainable Olympic Games. Environ. Plan. C 26, 882–905 (2008).

Andranovich, G., Burbank, M. J. & Heying, C. H. Olympic cities: lessons learned from mega-event politics. J. Urban Aff. 23, 113–131 (2001).

Chappelet, J.-L. Olympic environmental concerns as a legacy of the Winter Games. Int. J. Hist. Sport 25, 1884–1902 (2008).

Moore, S., Raco, M. & Clifford, B. The 2012 Olympic learning legacy agenda—the intentionalities of mobility for a new London model. Urban Geogr. 39, 214–235 (2018).

Temenos, C. & McCann, E. The local politics of policy mobility: learning, persuasion, and the production of a municipal sustainability fix. Environ. Plan. A 44, 1389–1406 (2012).

Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 1259855 (2015).

Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist (Random House, 2018).

Borucke, M. et al. Accounting for demand and supply of the biosphere’s regenerative capacity: the National Footprint Accounts’ underlying methodology and framework. Ecol. Indic. 24, 518–533 (2013).

Wiedmann, T. O. et al. The material footprint of nations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6271–6276 (2015).

Leonardsen, D. Planning of mega events: experiences and lessons. Plan. Theory Pract. 8, 11–30 (2007).

Scrucca, F., Severi, C., Galvan, N. & Brunori, A. A new method to assess the sustainability performance of events: application to the 2014 World Orienteering Championship. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 56, 1–11 (2016).

Laing, J. & Frost, W. How green was my festival: exploring challenges and opportunities associated with staging green events. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 29, 261–267 (2010).

Holmes, K., Hughes, M., Mair, J. & Carlsen, J. Events and Sustainability (Routledge, 2015).

Habicht, J. P., Victora, C. G. & Vaughan, J. P. Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. Int. J. Epidemiol. 28, 10–18 (1999).

Olympic Games Impact Study—London 2012 Post-Games Report (Univ. East London, 2015).

Cantelon, H. & Letters, M. The making of the IOC environmental policy as the third dimension of the Olympic movement. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 35, 294–308 (2000).

Monclús, F.-J. The Barcelona model: and an original formula? From ‘reconstruction’ to strategic urban projects (1979–2004). Plan. Perspect. 18, 399–421 (2003).

Olympic Games Impact Study (Center for Olympic Studies, 2020).

Fedorova, M. Postolimpiyskiy sindrom. Kommersant (17 December 2014).

Baade, R. A. & Matheson, V. A. Going for the gold: the economics of the Olympics. J. Econ. Perspect. 30, 201–218 (2016).

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics (Pearson, 2012).

Coalter, F. A Wider Social Role for Sport: Who’s Keeping the Score? (Routledge, 2007).

Billings, S. B. & Holladay, J. S. Should cities go for the gold? The long-term impacts of hosting the Olympics. Econ. Inq. 50, 754–772 (2012).

Reis, A. C., Frawley, S., Hodgetts, D., Thomson, A. & Hughes, K. Sport participation legacy and the Olympic Games: the case of Sydney 2000, London 2012, and Rio 2016. Event Manag. 21, 139–158 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank all who collaborated with us on the data collection. We are grateful to F. Bavaud, J. Grieshaber, J.-W. Lee, C. Guala and K. Peter for contributing to this paper in their own ways. The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) funded the research of this paper under the grant Mega-events: growth and impacts, grant number PP00P1_172891.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. designed the research, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.M., S.D.W., C.G., M.H. and A.L. developed the database. M.M., S.D.W., D.G., M.H. and A.L. collected and assembled the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Sustainability thanks Meg Holden, John Short and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Indicators for conceptual model of sustainability of the Olympic Games.

Supplementary Table 2

Bivariate correlations among indicators.

Supplementary Data

Output of statistical tests performed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, M., Wolfe, S.D., Gaffney, C. et al. An evaluation of the sustainability of the Olympic Games. Nat Sustain 4, 340–348 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00696-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00696-5

This article is cited by

-

The Olympics in crisis: challenges, reforms, and the path forward

The International Sports Law Journal (2025)

-

Unsporting climate

Nature Climate Change (2024)